With the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki with Japan in 1895, foreigners could set up and operate factories and workshops with power-driven machinery in the treaty ports of China. In order to expand their sphere of influence in China, foreigners quickly established many factories in these ports, increasing the export and import of goods. This contributed to the development of coastal treaty ports in China, especially in northern China, such as Tianjin and Dalian. The setting up of factories in treaty ports by foreigners also inspired the Chinese to set up factories in different parts of China, including the Chinese interior. Owners of the factories in the Chinese interior quickly found that it was difficult to transport the raw materials for manufacturing or the finished goods to the market. This problem was soon resolved by the rapid development of a railway network in the early 20th century. By 1913, over 6,000 miles of railway tracks had been laid. As a consequence, cities in the Chinese interior were connected to the coastal ports.

The rapid development of industries, ports and railways in China made possible the import and export of goods directly from cities within the country. Consequently, the importance of Hong Kong as an entrepot for Chinese trade declined. Within 20 years, the share of Hong Kong in China’s trade decreased from 41.41% in 1900 to 22.05% in 1920. The number of vessels involved in the China trade in 1900 was 84.9% of the total number involved in foreign trade, and the tonnage of vessels involved in Chinese trade was 55.3% of that involved in total foreign trade. Both the number of vessels involved in the China trade and the total number of vessels involved in foreign trade decreased in 1920. The percentage of vessels involved in the China trade fell to only 79.1%. The tonnage of vessels involved in the China trade saw a slight increase, but there was rapid increase in the total tonnage of vessels involved in foreign trade. Therefore, the percentage of tonnage of vessels involved in the China trade dropped to 41.7%. These figures clearly illustrate that Hong Kong’s trade was increasingly international and less reliant on China.[3]

| Hong Kong Foreign Trading Statistics (Including China) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel Number | Vessel Tonnage | |||||

| Total | China | % of China | Total | China | % of China | |

| 1900 | 46,365 | 39,348 | 84.9 | 17,247,023 | 9,543,329 | 55.3 |

| 1920 | 43,364 | 34,289 | 79.1 | 24,194,022 | 10,089,101 | 41.7 |

Table 1: Hong Kong Foreign Trading Statistics, 1900, 1920[4]

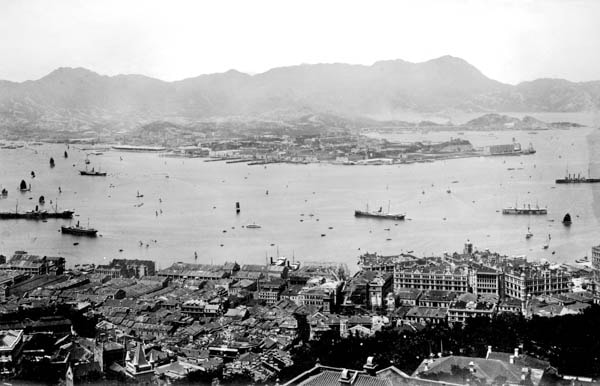

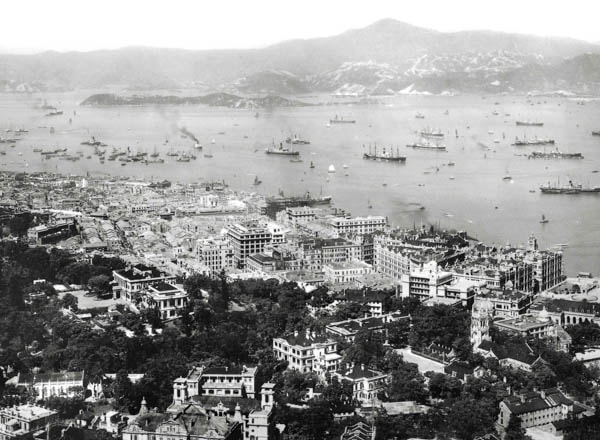

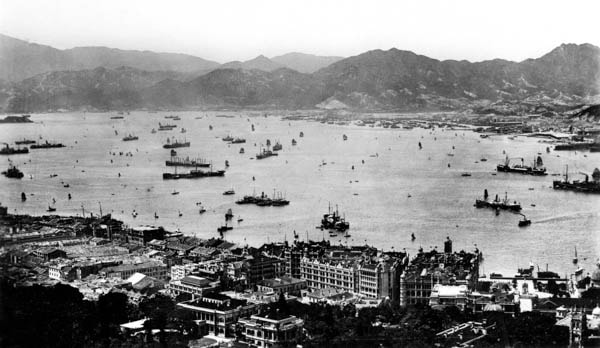

Plate 2: Hong Kong Harbour in the 1920s. Compared with Plate 1, it shows the growth in the number of vessels.

In response to the changes in Hong Kong trade and the increasing importance of the role of railways in the China trade, the Hong Kong colonial government believed that it was necessary to improve the facilities and the management of the harbour. The government decided to consult an expert harbour engineer in order to make recommendations on the improvement of the harbour’s facilities and management. In 1920, Messrs. Coode, Fitzmaurice, Wilson & Mitchell, MM.Inst. C.E., Consulting Engineers to the Crown Agents were appointed to investigate and make suggestions for improving harbour facilities and the management of the harbour in Hong Kong. After two years of investigation, the consulting engineers submitted a report in November 1922, in which they suggested reclaiming Hung Hom Bay for building warehouses and six jetties that could berth ships drawing 35 feet of water. They pointed out that a warehouse and new jetties in Hung Hom Bay could further facilitate the China trade by railway. Since the improvement scheme for increasing the depth and width of the Suez Canal would soon be completed, the engineers predicted that ships drawing 35 feet of water would be used in international trade within ten years. Thus, the warehouse and new jetties could enhance Hong Kong’s share of international trade.[5]

To solve the problem of the lack of wharves in Hong Kong, the engineers suggested three solutions. The first was to establish a Port Trust to take over and manage all existing wharves. The Port Trust would also manage all new wharves built in the future. The second solution was to allocate land to the existing wharf owners or other companies that were interested in building more wharves at their own expense. The third solution was that the government would be responsible for building new wharves, but these would be leased to and managed by private companies.[6]

For facilitating transportation between Hong Kong Island and Kowloon Peninsula, the engineers suggested that a ferry service for both horses and mechanical vehicles should be established. This ferry service would also serve to facilitate Hong Kong trade. [7]

After receiving the report, the colonial government referred it to the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce in 1923 and asked its members, comprising of European merchants, for their comments. Many members of the Chamber opposed the formation of the Port Trust. As for the Hung Hom Bay reclamation and jetties scheme, many members were basically supportive. However, apart from the Hung Hom Bay scheme, they also suggested that the government improve shipping and wharf facilities at West Point (Sai Wan today), build shipping and wharf facilities at North Point, build a wet dock at Kowloon Point (Tsim Sha Tsui today), and establish a passenger depot at Victoria (Central today).

To implement the engineers’ recommendations, the colonial government believed that it was necessary to have a separate department for managing port development. Thus, the Port Development Department was separated from the Public Works Department in 1924. In response to the Chamber’s opinions and suggestions, the government decided to undertake further studies on developing the port of Hong Kong. The government appointed John Duncan, a chartered civil engineer and port engineer, to be the head of the Port Development Department, and instructed him to propose a scheme to develop the port of Hong Kong. John Duncan submitted his report to the government on 12 December 1924.[8]

In his report, Duncan recommended a number of schemes for improving and developing the port, including building or improving berths and warehouses at North Point, Kennedy Town, Hung Hom Bay, Kowloon Point, and Wanchai Bay; developing ferry piers and a local passenger and cargo depot in Central; establishing a vehicular ferry service between Central and Jordan Road; improving the harbour of refuge at Causeway Bay and Mongkoktsui (western part of Mongkok today); and improving the system for recording harbour surveys, tide and current observations, sea conditions, and construction work in the harbour. Apart from these schemes, Duncan suggested that the government create an advisory port authority for assisting the government in formulating policies for port development. The advisory port authority would be responsible for studying and observing traffic and port conditions and making recommendations to the government based on the results of these studies and observations. Duncan suggested that it was not necessary for the government to adopt all these schemes and suggestions and implement them immediately. He suggested, rather, that the government should evaluate the necessity of each one and make the necessary amendments before implementation in order to cope with the needs of port development. [9]

After receiving the report, the colonial government referred it to the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce for comment. The Chamber co-operated with the Hong Kong Chinese Chamber of Commerce to hold two meetings in the City Hall in February and March 1925 to discuss the report. Members of the two chambers, government officials and John Duncan attended the meetings. After thorough discussion, all parties agreed that the government should first implement the schemes to develop shipping facilities at North Point and Kennedy Town, and also to establish the vehicular ferry service.[10]

Unfortunately, most of the schemes suggested by Duncan could not be implemented. With the success of the seamen’s strike in 1922, a number of incidents (including the murder of cotton-mill workers by the Japanese in Shanghai in May 1925, the killing of protesters by the British Police in Shanghai on 30 May 1925, and the massacre of protesters in Shaji on 23 June 1925), together with the promotion of anti-capitalism and anti-imperialism by the newly formed Chinese Communist Party, triggered a series of strikes and boycotts in Hong Kong in June 1925. This was the start of the Guangzhou-Hong Kong strike-cum-boycott (省港大罷工). Many Chinese seamen and labourers returned to Guangdong. In addition, the striking workers established a marine force to blockade Hong Kong harbour, eventually paralysing the Colony. The strike-cum-boycott continued for one year and four months, finally ending in October 1926 when the Guangdong Government, which wanted to switch the focus to the Northern Expedition for uniting China, announced its cessation.[11]

The strike-cum-boycott was ruinous to Hong Kong’s trade and shipping. The total number of vessels involved in trade plummeted from 764,492 in 1924 to 379,177 in 1925, and further decreased to 310,361 in 1926. The total tonnage of these vessels also decreased from 56,731,077 in 1924 to 41,469,584 in 1925, and continued to fall to 36,821,364 in 1926. The decline in shipping also had an adverse effect on the colonial government’s finances. The colonial government was facing deficits in 1925 and 1926. It tried to save money through restructuring some departments and cutting unnecessary expenditure. As the Governor Sir Cecil Clementi believed that it would be more cost-efficient and effective to merge the Port Development Department and the Public Works Department together for developing the port, the Port Development Department was re-absorbed into the Public Works Department in 1926. Because of this, most of the schemes suggested in Duncan’s report could not be implemented. In the end, only the proposal to establish the vehicular ferry and the suggestion to form an advisory port authority were implemented.[12]

| Hong Kong Trading Statistics (Total) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vessel Tonnage | Vessel Number | |

| 1924 | 56,731,077 | 764,492 |

| 1925 | 41,469,584 | 379,177 |

| 1926 | 36,821,364 | 310,361 |

| 1927 | 44,127,161 | 298,707 |

| 1928 | 44,883,765 | 300,316 |

| 1929 | 47,186,181 | 300,557 |

| 1930 | 40,190,612 | 94,090 |

| 1931 | 44,150,021 | 107,262 |

| 1932 | 43,824,906 | 104,115 |

| 1933 | 43,043,381 | 108,622 |

| 1934 | 41,914,022 | 93,754 |

| 1935 | 43,473,979 | 94,655 |

| 1936 | 41,731,016 | 83,571 |

| 1937 | 37,830,760 | 73,257 |

| 1938 | 30,962,756 | 67,007 |

| 1939 | 30,897,948 | 74,617 |

Table 2: Hong Kong Total Trading Statistics, 1924-1939[13]

In order to improve the standard of the ferry services, the colonial government passed the Ferries Ordinance in 1917. According to the ordinance, unless the government granted an exemption, no one could operate a ferry service without securing a licence from the government through public tender. The company that obtained a licence for operating a ferry service should abide by the required conditions stated in the tender for running the service in respect of, inter alia, the specifications for the ferries, fares and charges, and timetables. The company would also be required to pay royalties to the government. The “Star” Ferry Company, however, was exempted from the Ferries Ordinance, its services being already subject to regulation under an ordinance passed in 1902. From 1919 to 1921, the government granted three ferry licences to three different companies for operating ferry services between Hong Kong Island and Kowloon Peninsula, and between Hong Kong Island and the New Territories. As the services of these companies were poor, the government invited tenders again when the first licence expired in 1923. The Hongkong and Yaumati Ferry Company Limited (HYF), established in 1923, was granted the ferry licence. The HYF was managed by a group of leading Chinese merchants in Hong Kong, who were willing to put in effort and money to improve the ferry services. Because of this, the government granted a number of ferry licences to HYF for operating other ferry services in the 1920s and the 1930s.[14]

As the “Star” Ferry had been providing a vehicular cross-harbour service by using lighters with cranes and cradles provided by the Kowloon Wharf and Godown Company since 1918, it expressed interest when the government decided to consider Duncan’s scheme for establishing a vehicular ferry service in 1924. The government amended the scheme suggested by Duncan and finally proposed the establishment of a vehicular ferry in 1928. With the construction work of the vehicular ferry piers at Jubilee Street and Jordan Road soon to be completed, the government invited tenders for the vehicular ferry service in 1932. Since the “Star” Ferry operator did not agree with the conditions for operating a vehicular ferry service as stated in the proposal amended in 1928, it decided not to submit a tender. As an enterprising company, the HYF submitted tenders for the vehicular ferry licence. Since the HYF could fulfil the requirements set by the government, and as it had an exemplary performance record, the company was awarded the licence. The vehicular ferry service finally started on 1 January 1933.[15]

The government also accepted Duncan’s suggestion to establish an advisory port authority. After five years of consideration and preparation, the Harbour Advisory Board was set up in 1929 to provide the government with advice on the development and management of the port. The board consisted of twelve members, including government officials and representatives from the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce and the Hong Kong Chinese Chamber of Commerce. The Harbour Master was the chairman of the board. However, the government dissolved the board in 1931 and established a smaller Harbour Advisory Committee, whose function was the same as the board’s. The committee consisted of seven members, including government officials and unofficial members nominated by the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, the Chinese community, and the Royal Navy. The Colonial Secretary was the chairman of the committee.[16]

The conclusion of the strike-cum-boycott was followed by the outbreak of the Great Depression, which affected the global economy in the early 1930s. Meanwhile, the Japanese had launched the invasion of Manchuria in 1931, extending their aggression to the rest of China in 1937. Within a short period of time, the coastal area of north-eastern China was occupied by the Japanese, with the coastal area of south-eastern part of China following after 1937. Guangzhou and Shenzhen were occupied by the Japanese in 1938 and 1939 respectively. These factors adversely affected trade and shipping in Hong Kong. As shown in the Hong Kong Total Trading Statistics, the total tonnage of vessels involved in trade rose from 36,821,364 in 1926 to 47,186,181 in 1929. But after 1929, total tonnage fell precipitously to 30,897,948 in 1939. The number of vessels involved in trade dropped from 310,361 in 1926 to 300,557 in 1929 and declined further to 74,617 in 1939. (Table 2)[17]

As companies in Europe and the United States went under during the Great Depression, the number of vessels entering Hong Kong that were involved in European, American and other countries’ trade decreased. On the other hand, the Japanese invasion of the north-eastern regions of China made Hong Kong once more an important international port for the China trade, at least until 1937. Hong Kong’s share in the China trade therefore increased. In 1926, the number of vessels involved in the China trade fell to only 63.3% of the total number of vessels involved in foreign trade. The tonnage of vessels involved in the China trade rapidly declined to only 22.9% of that of vessels involved in foreign trade. In 1931, the percentage of vessels involved in the China trade increased to 77.9%, and the share of the total tonnage of vessels involved in the China trade rose to 41.5%. Nevertheless, still less than half of Hong Kong’s trade was with China.[18]

The number of vessels involved in the China trade and foreign trade declined further in 1937. The number of vessels involved in the China trade was 73.4% of that of vessels involved in foreign trade. The year also saw a decrease in the tonnage of vessels involved. The tonnage of vessels involved in the China trade declined to only 35.4%. In 1939, the Japanese occupation of the south-eastern coastal region of China led to a plunge in the total number of vessels. The number of vessels involved in the China trade plummeted to 43.6% of that of vessels involved in foreign trade, accounting for only 19.5% of the total tonnage of vessels involved in foreign trade. These figures reflect that Hong Kong’s trade again became less dependent on China near the end of the 1930s.[19]

| Hong Kong Foreign Trading Statistics (Including China) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel Number | Vessel Tonnage | |||||

| Total | China | % of China | Total | China | % of China | |

| 1926 | 30,231 | 19,133 | 63.3 | 28,371,101 | 6,508,139 | 22.9 |

| 1931 | 51,801 | 40,360 | 77.9 | 41,933,748 | 17,382,454 | 41.5 |

| 1937 | 33,782 | 24,802 | 73.4 | 36,191,724 | 12,814,074 | 35.4 |

| 1939 | 23,881 | 10,410 | 43.6 | 29,196,466 | 5,698,623 | 19.5 |

Table 3: Hong Kong Foreign Trading Statistics, 1926, 1931, 1937, 1939[20]

With the passage of the Piers Ordinance in 1899, the colonial government granted pier leases to the owners of all piers in Hong Kong for 50 years until 1949. The owners of the piers were required to pay rent to the government. For piers built after 1899, the government also granted to the owners leases that would expire in 1949. In 1938, the government announced that the pier leases would not be renewed after expiring in 1949. This was because the Governor, Sir Geoffry A. S. Northcote, wanted to conduct a study on managing and developing the port in order to decide whether the port should be managed by the government, or by a Port Trust, or by private enterprises, or by a combination of these methods. In 1940, with the assistance of the Secretary of State of the British Government, the colonial government appointed Sir David J. Owen, the former General Manager of the Port of London Authority, to investigate port facilities in Hong Kong and to make suggestions for future port development and administration. Owen submitted the report in February 1941. Unfortunately, due to the invasion and occupation of Hong Kong by the Japanese from December 1941 to August 1945, discussion on the report was suspended until after the British reoccupied Hong Kong in September 1945.[21]

Notes:

- [3]T. N. Chiu, The Port of Hong Kong, pp. 34-37; Reports of the Harbour Master, 1900, 1920; ‘Synopsis of External Trade 1882-1931’, 載於中國第二歷史檔案館、中國海關總署辦公廳:《中國舊海關史料(1859-1948)》(北京:京華出版社,2001),頁152-157、174。

- [4]Ibid.

- [5]Report of the General Committee of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, 1923, pp. 1-17; John Duncan, ‘Report on the Commercial Development of the Port of Hongkong’, Hong Kong Sessional Papers, 29 December 1924, pp. 111-113.

- [6]Report of the General Committee of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, 1923, pp. 1-17.

- [7]Ibid.

- [8]Report of the General Committee of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, 1923, pp. 20-43; John Duncan, ‘Report on the Commercial Development of the Port of Hongkong’, Hong Kong Sessional Papers, 29 December 1924, pp. 114-116.

- [9]Report of the General Committee of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, 1924, pp. 101-110; John Duncan, ‘Report on the Commercial Development of the Port of Hongkong’, Hong Kong Sessional Papers, 29 December 1924, pp. 143-168.

- [10]Report of the General Committee of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, 1925, pp. 57-63.

- [11]中國海員工會廣東省委員會:《廣東海員工人運動史》(廣州:廣東人民出版社,1993),頁76-90;鄧中夏:《中國職工運動簡史》(北京:人民出版社,1979),頁222-232、242-254;Hong Kong Annual Report for 1925; Hong Kong Annual Report for 1926; Endacott, A History of Hong Kong, pp. 289-290.

- [12]Reports of the Harbour Master, 1925 - 1926.

- [13]Reports of the Harbour Master, 1925 - 1939.

- [14]David Johnson, Star Ferry: The Story of a Hong Kong Icon (New Zealand: Remarkable View Limited, 1998), pp. 17-18, 24-27; CO129/454/95-103, ‘Yau-Ma-Ti and Mong Kok Service’ in Enclosure 1 of the letter from Claud Severn, Officer Administering the Government, to Viscount Milner, 7 April 1919; “The ‘Star’ Ferry Company Ordinance 1902”, Hong Kong Government Gazette, 17 December 1902, p.2205; “The ‘Star’ Ferry Company Limited By-laws”,Hong Kong Government Gazette, 24 December 1902, p. 2235; “’Star’ Ferry Co. Ltd.”, Hong Kong Hansard, 9 December 1902, p.81; CO129/454/55-56, Letter from Claud Severn, Officer Administering the Government, to Viscount Milner, 7 April 1919; CO 131/54/366, ‘Ferries Ordinance, 1917’, Minutes of 46th Meeting of Hong Kong Executive Council 1918, Hong Kong Executive Council, 1918, Vol. 2, p.45; CO 131/54/409, ‘Ferries Ordinance, 1917’, Minutes of 1st Meeting of Hong Kong Executive Council 1919, Hong Kong Executive Council, 1919, Vol.1, p.2; ‘Questions from the Unofficial Member Ho Fook to the Government’, Hong Kong Hansard, 15 May 1919, p.27; Hongkong and Yaumati Ferry Company Limited, The Hongkong & Yaumati Ferry Co. Ltd.: Golden Jubilee, 1923-1973 (Hong Kong: Hongkong and Yaumati Ferry Company Limited), pp. 6, 13.

- [15]Hong Kong Hansard, 4 September 1930, p. 142; ‘Vehicular Ferry’, The Hongkong Telegraph, 22 March, 1932, p. 12; Johnson, Star Ferry, p. 63; CO129/526/34-45, Letter from W. T. Southorn, Officer Administering the Government, to Lord Passfield, 22 April 1930; ‘Vehicular Ferry, Hong Kong – Kowloon’, Hong Kong Sessional Papers, 1928, No.6.

- [16]Report of the General Committee of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, 1929, pp. 42-44; Report of the General Committee of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, 1931, p. 13.

- [17]Reports of the Harbour Master, 1924 - 1939.

- [18]Reports of the Harbour Master 1926, 1929; Reports of the Harbour Master and Director of Air Services 1931, 1937, 1939; Yu Kwei Cheng, Foreign Trade and Industrial Development of China: An Historical and Integrated Analysis through 1948 (Westport: Greenwood Press, Publishers, reprinted 1978), pp. 48-49, 134-135; ‘Synopsis of The External Trade of China, 1882-1931’, 載於中國第二歷史檔案館、中國海關總署辦公廳:《中國舊海關史料(1859-1948)》(北京:京華出版社,2001),頁175。

- [19]Ibid.

- [20]Ibid.

- [21]Report of the General Committee of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, 1938, pp. 18-20; Report of the General Committee of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, 1940, pp. 36-38; David J. Owen, Future Control and Development of the Port of Hong Kong, 24 February 1941.

Part 1 Chapter 4.2 - Growth of the share in international trade and the development of the port